The novel coronavirus 2019 pandemic was declared a national emergency in the U.S. by the President on March 13, 2020. Far along the timeline, we’re now just a few weeks away from the 6-month mark here. So much was unknown at that time. Fear and anxiety were the rule… and seem to be, yet. Models were estimating over 2 million US deaths without lockdowns, quarantines, and social distancing. (These numbers were later shown to be based on Neil Ferguson’s “unreliable” computer code, although that’s been a hotly debated and politicized topic, as well.)

“Flatten the Curve!” became the crying call across media and politics. The argument was that via heavy interventions, the spread of the virus could potentially be slowed. A massive peak might be avoided. Otherwise, the nation’s health care capacity would be overwhelmed and perhaps hundreds of thousands of Americans would be left without care. Also, by slowing the spread and flattening the peak of cases, more time would be allowed in order to bring down the death toll from over 2 million to maybe 250,000. That would also allow time for herd immunity and vaccine development.

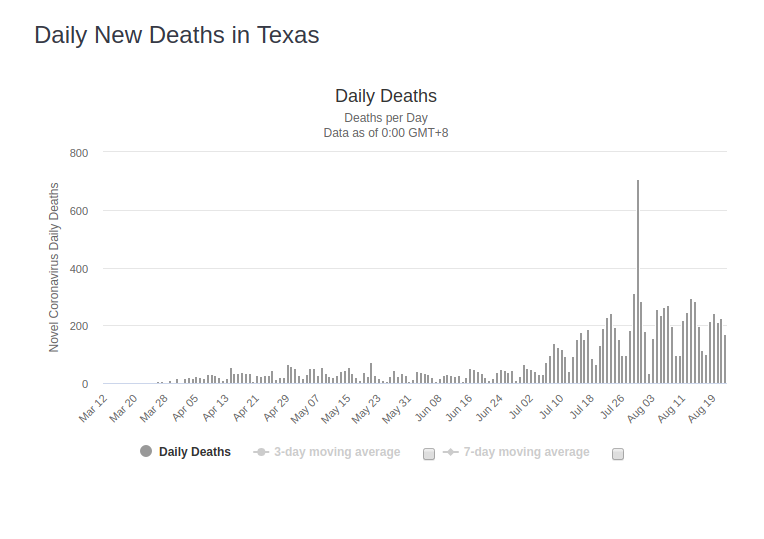

As the situation was looking better, perhaps by June, by July there was a “second wave” feared as virus numbers and deaths began to increase again. In retrospect, it doesn’t appear that this was another wave of a returning viral infection, but the movement of the virus from the coasts (especially New York) towards more central states. My home state of Texas, especially Houston, faced fears of overwhelmed hospital and ICU capacity. As Texas had done very little mandatory social distancing or masking, this was seen by the media and lockdown advocates as justified punishment for lax behaviors. I heard as much in talk from staff and doctors in my own hospital environments in Pittsburgh, PA. Fortunately, Texas had a quick peak at the end of July that lasted a week or two, and has slowly trended downward. Houston’s ICUs reached baseline capacity at that time, but never experienced stress on their Phase 2 overflows nor did Texas cities require use of any makeshift facilities for patients.

At the six month mark, the original calls and mandates for a few weeks of curve-flattening lockdowns have extended in many ways until today, with no foreseeable return to normalcy. The expectations of case flattening and hospital capacity preservation have morphed into a demand for zero positive tests. Masking mandates are the norm. Some schools are opening with hybrid online and in-person classes. Many classes are entirely online and/or remain in various stages of uncertainty. Parents are caught between figuring out child-care, education, their role in supervision or homeschooling, their own work options, and navigating new financial situations caused by the economic turmoil of lockdown.

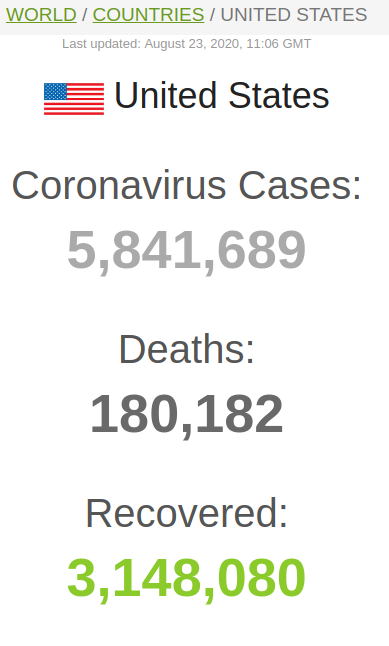

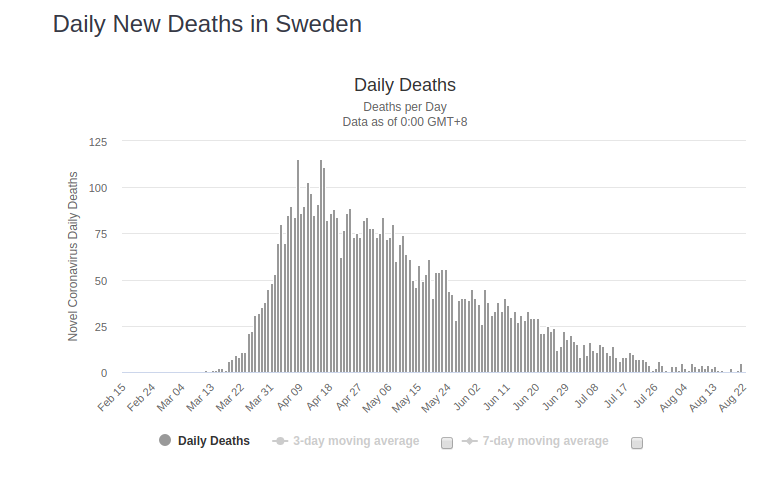

Many will argue for the appropriateness of these measures, and potentially even call for stricter enforcement. There have been, after all, 180,000 deaths attributed to this virus in the US, to date. That’s a big number, and it isn’t over, yet. Bad flu seasons here may hit 60,000 to 70,000 deaths. People die from this – primarily the elderly and otherwise ill – but many young and healthy people are afraid of contracting or spreading the virus. The numbers, testing and risks can and have been debated everywhere, with little consensus anywhere. I’m still a proponent of Sweden’s low intervention model that isolated the sick and ill, leaving much of society to function with caution,… but that opinion is sure to ignite a heated debate!

What has been reinforced to me throughout this period is less about the behavior of viruses and more about the nature of humans. We all have different risk tolerances, reading affinities, personality traits, isolation tolerance, employment needs, life experiences, political and world views, sets of biases, vulnerabilities, baseline health status, levels of regard for experts and authority figures, tendencies towards logical fallacies, and different intelligence levels – although this last may be among the least influential. All of these factors, and certainly more, contribute to our personal attitudes and responses. I work with a lot of presumably intelligent physicians and professionals, and their opinions regarding the risks of the virus and the costs of the societal interventions are as polarized as those of the general public. Does that mean that we’re all seeing different data? Or that many are misinterpreting it? Or are too stupid to understand it? Or just that our personalized calculations and subjective value sets lead to us all to divergent opinions and choices?

In our increasingly polarized (or at least electronically amplified) society, some may believe that my comparatively reduced concern for viral risk is callous, cavalier, poorly reasoned, even perhaps “murderous.” Simultaneously, I may look at some of the die-hard lockdowners as simple-minded, automatons, catastrophists, incapable of broader perspective and cost analysis. Where is the consensus to be found? I think the answer is: there is none. Our views are often irreconcilable. And the more that enforcement, shaming and threats are utilized to coerce others to comply with our views, the greater the animosity, disregard and division. Of course, this dynamic is clearly extrapolated across political, cultural and religious spectra. So, what is to be done to find some peace and unity?

For one, self-aware adults can realize that we are often wrong in our assumptions and “certainties.” Our impressions and convictions can be (and often are) incorrect. We all have information biases and knowledge deficits. We misunderstand probabilities and likelihoods. We cannot humanly contemplate or predict the breadth of consequences for ourselves and others. We all have many individual factors that influence our opinions. Recognizing these imperfections and variations can provide room for understanding, or at least tolerating, others.

Of course, the entire role of politics and media is to exacerbate then exploit myriad differences towards emotionalized polar extremes, rather than to foster calm, discourse and understanding, which would do little to drive the machinery of ratings, money flows, votes and power distributions. So, secondly, maybe a healthy move that could save and value more lives than lockdowns (especially in the realm of foreign interventionism) would be to turn off the media and the political circus.

P.S. Of note, (pre-dating our most recent iteration of discord,… which really is nothing particularly new over the centuries) here are some interesting works that I’ve audiobooked this past month. These touch on the biases and the flaws in our thinking, which should make us all less certain of our “convictions.”

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds, by Michael Lewis. “Forty years ago Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky wrote a series of breathtakingly original studies undoing our assumptions about the decision-making process. Their papers showed the ways in which the human mind erred systematically when forced to make judgments about uncertain situations. Their work created the field of behavioral economics, revolutionized Big Data studies, advanced evidence-based medicine, led to a new approach to government regulation, and made much of Michael Lewis’ own work possible. Kahneman and Tversky are more responsible than anybody for the powerful trend to mistrust human intuition and defer to algorithms.”

Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman. “Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman’s seminal studies in behavioral psychology, behavioral economics, and happiness studies have influenced numerous other authors, including Steven Pinker and Malcolm Gladwell…. Two systems drive the way we think and make choices, Kahneman explains: System One is fast, intuitive, and emotional; System Two is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. Examining how both systems function within the mind, Kahneman exposes the extraordinary capabilities as well as the biases of fast thinking and the pervasive influence of intuitive impressions on our thoughts and our choices.”